Now, when swimmers all over the world are having difficulties with swimming, the historian and member of the Henleaze Swimming Club Susie Parr reminds us that the rich swimming culture is quite ancient — and we will all start swimming again soon, like so many before us. Our reading recommendation is The Story of Swimming. Read a little more about this rare book

The Story of Swimming, a book that took me ten years to write, was published in 2011. I wrote it because I wanted to try and understand my compulsion to jump into water at any opportunity by exploring the social and cultural history of swimming in Britain’s rivers, lakes and seas. In the book, I tracked references to open water bathing from the earliest times up to the present day.

My sources included myths, folklore, historical records, literature, art, and – latterly – social media. I read how invading Roman soldiers using swimming as a military tactic and appropriated native sacred springs. Anglo Saxon literature (Beowulf in particular) and the Viking sagas gave dramatic accounts of warriors engaging in swimming competitions in the open sea. Later literature documented how medieval knights, unsurprisingly, struggled to stay afloat whilst wearing full body armour. De Arte Natandi (1587) provided instruction on swimming for gentlemen, illustrated with charming woodcuts showing naked bathers on riverbanks in an Elizabethan landscape. Sir John Floyer’s History of Cold Water Bathing (1715) provided plentiful evidence of people using immersion in cold water to treat various ailments, from canker to ‘Hypochondriac Melancholy and Windiness.’

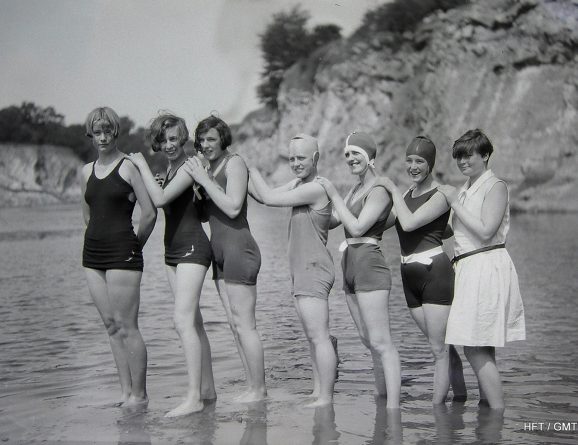

Sea bathing for health really took off in the mid/late 18th century, the wealthy infirm patronising seaside settlements such as Scarborough, Tenby and Weymouth. These evolved from humble fishing villages into elegant and urbane resorts. At the same time, leading Romantic poets bathed and swam. For Wordsworth, immersion in lakes and rivers was symbolic of his interfusion with the natural world and his engagement with local landscape. Byron was a strong and heroic swimmer, racing across the Venetian lagoon and broaching the Hellespont. Once the railways arrived, ordinary people were able to flock to the seaside and into the briny. The crowds on the beaches led to a proliferation of rules and regulations about who could swim, when, where and how.

After the second world war, the British seaside went into decline as jet travel and package holidays opened access to warm, blue seas and pristine beaches. Our cold, murky and polluted waters lost their appeal. Tidal pools and lidos fell into disrepair around the country. Published in 1999, Roger Deakin’s Waterlog flagged up the forgotten attractions of our native waters. Deakin’s watery journey across Britain was followed by Wild Swim by Kate Rew (who founded The Outdoor Swimming Society in 2006), and a series of books by Daniel Start on ‘wild’ activities. Wild swimming gradually started to gain popularity, as bathers re-connected with nature, dodged rules and regulations and escaped the chemical fug of the indoor pool.

Nearly ten years after The Story of Swimming came out, a lot has changed. Open water swimming has become a pursuit enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of people in the UK. The OSS started off with 300 members and now has 100,000, with half a million visiting its website. There are now ten times the number of open water swimming events in the UK than there were two years ago. From the Blackpool Pier to Pier to the Bantham Swoosh, more and more swimmers are taking the plunge in UK waters. Meanwhile, traditional local swims such as the New Year Loony Dook in Broughty Ferry are carrying on as they have done for decades, albeit with more participants year on year.

Books about open water swimming proliferate, some addressing the mental health benefits of immersion in the cold (see The Outrun and Dip: wild swims from the Borderlands). Short films about outdoor swimming are also having a moment. Research into the health benefits of immersion in cold water is accumulating; more people than ever are engaging in year-round swimming, some taking on extreme challenges of prolonged exposure. Ironically, just as we are starting to understand the benefits of cold water, we realise the world is warming at an alarming pace. Lewis Pugh has just swum under a melting Antarctic ice sheet to raise awareness of climate change. And Brexit means that the UK will be able to set it’s own bathing water quality standards.

But local swimming communities are popping up everywhere. A few years back, the marine pool at Clevedon was neglected, rubbish strewn, and uninviting. It has been refurbished by locals and now is used year-round by swimmers. Full moon, dawn and sunset swims draw healthy numbers; swimmers repair to the nearby pub to warm up and socialise, or at least they did until the Covid virus arrived. The groups also have a strong on-line presence – people requesting buddies for a night swim or asking after mislaid goggles. Used to being a lone swimmer, I am amazed at the friendliness and warmth of such groups and so happy to have companions in the water. We may have to keep our distance from fellow bathers at the moment, but open water swimming is here to stay.

Susie Parr

Source: www.outdoorswimmingsociety.com